One Saturday morning, my brother and I were watching TV when Mum came downstairs and said, "Boys, I've met a man." Jack was nine at the time, but at seventeen, I considered myself Mum's agent, and as agent, I thoroughly approved, and said so. And Mum might have felt the same as me, because she next had to check we were happy with the details.

"He's a man on the internet."

Today, there are many men on the internet. (The internet thrums, surges with men, to the point where good people often decide there are, if anything, too many, and take a break.) But it was 2002, and the idea of meeting a man on the internet was about as plausible as, say, buying a book on the internet.

It’s even stranger when you think about my Mum, sixteen years ago. The way she told us, sidling in to request that she be able to look for love in a manner that wouldn't disrupt our cartoons, carried the reserve she had when it came to men. Her relationship with Dad hadn't been a happy one, in a way that I never fully understood because—and I'm only grasping this now—she hid it so well, two closed doors away from wherever I was in the house. If he ever did Dad stuff, like picking me up from school or putting a pizza in the oven, I thought he was unbelievably cool doing it. Perhaps because he was so funny. Perhaps because whatever he was doing, it seemed like he had better things to do. Perhaps this is why he was only my Dad about 50% of the time.

After he left to become my Dad 0% of the time, Mum made some half-hearted attempts to meet people, but what do you do when you're a primary school teacher in a small town in South East England? Mrs. Claire Mitchell was every child’s favourite, and she was always invited to the gatherings of well-meaning parents, but she felt keenly the sense of other people’s charity, and she winced every time she was summoned to yet another friend’s granite kitchen island to meet “someone we think you’ll really like.” The daytime? Most of her colleagues were children. And she didn’t want to stand around at the bar of the Slug and Lettuce, waiting for divorcées to talk to her (“Didn’t you teach my Faye?”). Or, if she did want to hit the town, she buried it deep because she had two needy boys to look after. When it comes to love, honest physical serendipity is the dream, but when you spend years walking the world without meeting anyone remotely like you and single, well. You could meet anyone online. A millionaire stepfather, imagine that. In that moment in front of the TV, I did.

Dave—davebyus, if we're talking usernames—was a locksmith in Visalia, California. That’s California, America, the America of films and rich friends’ holidays. Friends with two parents. Dave had experienced his own marriage falling apart, had his own children, and like Mum, hadn’t come to the internet asking for love. Even if OKCupid had existed at the time, I think they’d both given up on love, or assumed they’d had their fair share of it in their lives already. They found each other without looking. “You know I’m doing this writing course online,” Mum said to us. I’d read her short stories, written in round teacherly handwriting on A4 lined paper. “He’s doing it too.” Some pre-algorithmic twist of fate had put them in the same study group of the Writers’ Village University “f2k” course, and there they’d started discussing each others’ work, and then each other, Mum taking the house phone up to her room or out to the garden for an hour at a time. Yes, I’d noticed this, when I looked up from Final Fantasy VIII for long enough. After she worked up the courage to send him her address, he sent her letters and mixtapes like a true courting Californian: I remember a burned CD of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young with a handwritten tracklist and doodles on the back. And now that I knew about him, I got mail, too. A handwritten letter with a dollar, the first I’d held, and a pocket-sized copy of the Constitution. The letter was short and funny, just one scribbled leaf torn from a reporter’s notepad. Something about it being sunnier there. “Your mom tells me you’re about to study politics.” It ended with a dirty limerick. Alright, I thought, as I folded the dollar into my Animal surfer’s wallet. You can stay.

Two months after the letter, Mum flew to California for one week, and Jack and I settled at our grandparents’, in the room where Mum and her sister had slept as children. We spent a long day with the usual distractions, kicking the deflated ball against the garage wall and watching animated Robin Hood. In the evening, the telephone rang in the study. Grandma went upstairs to answer it, then called down for me. An endless climb later, I put the phone to my ear, and:

“He’s wonderful. He’s asked me to marry him, and I’ve said yes.”

She came back happy. Happy, in a way I’d assumed parents could not be. Hungry for life, eager for time to move on to the next, brilliant thing. And the next thing would be brilliant, for Dave made plans to visit us in the summer. We drove to Heathrow Airport to pick him up, stood in front of the tiny door marked Arrivals, and waited for this man to emerge onto British soil. An hour went by. The people from his LAX flight passed us, hugged their families. Then Mum’s flip-phone rang, and she scrambled in her bag for it.

Dave had been held at the border. A lone man who’s not dressed for business and hasn’t left his country in the 50-something years of his life raises eyebrows at Heathrow. He shared such earnest excitement with Mum, I imagine he earnestly told an unsmiling border officer he was going to visit the family of his fiancée who he met on the internet; see, here’s the baseball bat I’ve brought her children, they don’t know me yet. Mum was summoned to Immigration from the other side, and while we waited at the gate, they sat parallel interviews: yes, they’d met online. A writing website, yes. Yes, they were getting married—no, not yet, he has a ticket home, we’re doing it all above board, we’re good people. Another hour later, he was released—they were released, together, and walked out of Arrivals looking like they had always been together and free. He shook my hand like an equal, but after that I sat with Jack in the back of the car where I should have always been. Dave sat in the front with Mum, and suddenly, finally, our little car was full of family.

The fortnight passed like a film. The places we’d always been felt renewed: the park, the kitchen, our little town—now truly inhabited by a complete us, with this happy scarecrow of a man gazing at everything, mouthing every -shire and -borough on the road signs. Jack and I took him to the park: a little field behind the house bordered by the trees, the church, and the town cricket club. It turned out I was terrible at baseball, he was terrible at football—our football—and Jack was brilliant at both. And just as that incredible life began to feel like something we deserved, Dave had to go home, to transform back from vital reality into a voice, a letter, a username. Something had changed for me, though. School was charged with a new energy. I represented a family, with a family’s future, not just an individual life, trying to sweep up the past into something whole. I told my best friend Alex about “Dave in America”; maybe I would go to college there. Half the school (the half that could get in) made a pilgrimage to see American Pie 2, and I thought that even the life of its most unfortunate character would make for a good future, if only I could get it.

The summer holidays: my memory of the Valley is all senses. Visalia was a four-hour straight-line drive from LAX through desert and vineyard, and Dave’s old pickup did it both ways, his hand on her thigh the whole return journey, in a way that seemed to me like it must have always been there. Dry heat on the dust, the shocking blast of an air-conditioned Save Mart doorway, the radioactive mouthfeel of a huge slurpee. In the Sequoia National Forest, the sounds of a bear snuffling near our tent at night; the thump of a fist-sized pinecone on the forest floor in the morning. And one scene, remembered in full: a truck drive up winding mountain roads into that forest, listening to Moon Safari by Air and feeling like Dave was confidently driving us up out of the sad, small lives we had once led and into a new world.

Today we are all used to the idea of the internet granting us an alternative life. A new name, new values, friendships, status. But this felt like new life beyond a login. In this life, whenever I spoke, people turned to listen. People overheard me and gasped, “Harry Potter!” The most famous English boy in America. (You know, the boy who slept in a cupboard under the stairs, until a letter arrived and changed everything?) The first house party I went to was in the apartment above Dave’s. A confident girl named Georgia pointed at the Homer Simpson poster on her wall and demanded: “Do you know who this is?” I crept back downstairs at 2 a.m. as the party drifted to a close. My head buzzing with cicadas and booze, I wondered what miracle had given me this body to wear, and if I’d ever have to give it back.

Girls actually talking to you. Parties where you belong. The measures of meaning in a heterosexual teen boy’s life are so simple. But each of us was given what we needed: Jack, a real male role model who was there when he said he would be; Mum and Dave, someone to laugh with, make plans with, play CDs to. When we came home for the new school year, I could not say which life was the real one. Only one had a defined future. They’d get married, we’d apply for green cards, and all the while I would sit my A-levels and finish a British education, while trying to work out how I might pay for US college. An outlandish, half-formed plan, but stranger things had already happened.

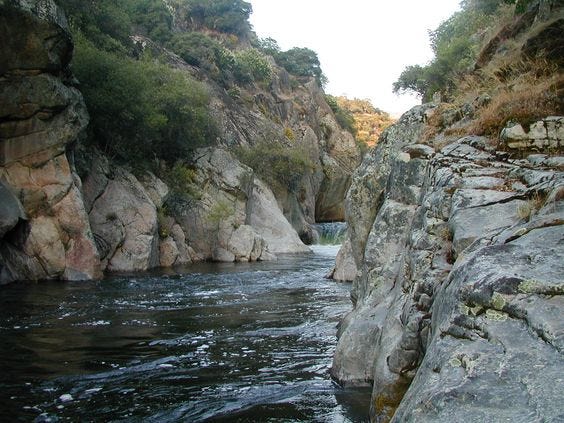

In September, we returned for the wedding. Just Mum, Jack, and me. With family supportive but absent, it felt like an elopement. Mum and Dave couldn’t afford a full service, and they didn’t really want one. Instead, we made that same drive up the mountains, the four of us in a rented Dodge Ram, followed by our friends from Dave’s apartment and his pastor, also called Dave. We couldn’t reach the summit as planned because it had snowed and we didn’t have tyre chains, so our convoy became a congregation halfway up at a mountain creek. Pastor Dave led us to a rocky outcrop, tiered geology cascading around and holding up the widest of skies above us. Mum and Dave stood before him, and we stood beside our Mum, and witnessed only by five friends and a rushing river, the pastor asked a teacher and a locksmith who’d met on a forum if they would take each other as husband and wife.

They’d written their own vows. We have the magic and the mystery, Mum said. The high air whipped her words away as she spoke them and made her tresses dance. We’d never seen her like this. Jack smiled at me. We came down from a different mountain than the one we’d climbed.

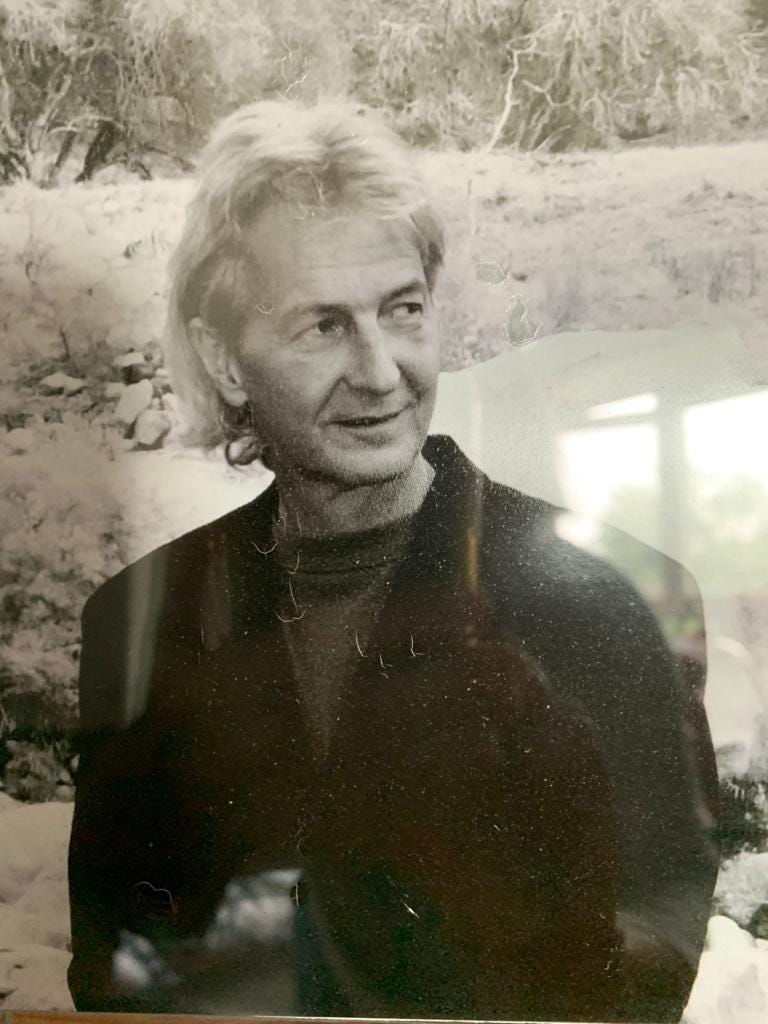

The three of us returned to England to pack up our affairs, guide immigration papers through channels (Claire Byus, the well-practiced new signature read), and let me take my exams. Until our new life began, we had to pretend the old one was still valid. The internet and phone was where Mum and Dave (Dad? Not yet, but I knew it could happen) had their extended honeymoon. And of course, they kept writing fiction, sending each other stories. It makes me sad that at the time, I didn’t really care that much, and I never asked Dave to read his writing. Years later, the website where they’d met bought and published one of Dave’s stories, and as I began to write, I studied it. A Wish For Jackie was 1,708 words of perfectly formed, wide-eyed-but-wise fable. It was anchored by emotion, quietly meticulous, and unpretentious. A Californian locksmith of a story.

Dave had never met Mum’s parents, and since they’d looked after Jack and me for that first-ever visit, he owed them a visit of his own. He came for Valentine’s Day, 2004, a cold week: we played Scrabble in our little kitchen; lost him, for a heart-stopping half minute, in Central London; braved icy wet wind on the battlements of Windsor Castle. On the last day, he sat on the sofa with a box of tissues and a Lemsip. Surely it wouldn’t hurt to stay a couple of days and rest? But there was nobody to run the shop. Keys always need cutting. We prepared to return to the old life, a marriage held together by Atlantic cable.

That’s how Dave called Mum the next day, to say he’d gone to the Kaweah-Delta Medical Center, been diagnosed with “a bad cold, maybe asthma”, and sent home with an inhaler to look after himself. He had a novel I’d lent him; he’d hole up in bed with that and let the sickness wash out of his lungs. He’d stay in touch. We went to school, and school, and work; we lived, and waited. That’s what you do when you can’t be there.

We got home, and the phone rang upstairs in Mum’s room, as promised. She called me up. An endless climb later, I was sitting on the bed next to her. Mum hadn’t put the phone on speaker but I could hear that it was Sarahelena, Dave’s downstairs neighbour. We barely spoke to her, had no cause to.

“Are you sitting down?” she said. So people really say that, went my dumb thought.

I went downstairs first. To get out of the bedroom where time wouldn’t budge. So I saw Jack, standing at the bottom of the stairs below me, looking up in a question. Nobody had taught me how to say such a thing any more than they’d taught me how to hear it. It shouldn’t be something that’s just blurted out to you; you should already know, you should see it happening slowly, in a quiet room, you should have time to make peace with the idea that—

“Dave’s dead.”

My brother’s face crumpled. That was the moment when I understood how much Jack really loved him. And how much I loved him, too. Behind us, halfway up the stairs, Mum sagged to the landing, and let out a scream that filled our house. A single, violent noise from the centre of her.

In all the travel and tearing up visas and packing up lives that followed, all of the grief and awkward pity and silence that came to fill the empty seat in our lives to come, she would never repeat that noise where we could hear. She didn’t have to, because its meaning was clear: the end of everything, for all of us, forever.

It seems incredible to me now, at 33. Sitting at the kitchen table and sifting through the story while my loving partner sleeps in—my impossibly special someone, in a bed just a room away, and yet we communicate over the internet more often than Mum did with her husband in another country. Would they have sent each other emojis, GIFs? What would our family Whatsapp group be like? Mum did not find another partner—you can’t follow that—but carried on as though nothing had happened. Or so it might seem, but there are clues of the magic it worked within her. One big thing: she became a foster parent, using the best of her teaching to show desperate children a world as new to them as the Valley was to us. If your heart can send you across the sea via a messageboard, what can’t it do?

The small things are big things, too: the American flag on the wall of Jack’s room, and the dollar, framed, in mine, like waking from a dream of the sea to find a shell in your pocket. And the name Claire Byus, once signed, was never undone. The laminated Comic Sans labels on classroom doors carried the same name that fell from the lips of a thousand grateful students: Mrs. Byus. She gets stopped in our hometown by those children now, some as adults with children of their own. She doesn’t tell the story to any of them, of course, and neither Jack nor I tell it much to anyone else, perhaps because it sounds so sad that it feels like handing someone a thing they don’t know what to do with. Perhaps because it seems so much like a story, and every year that passes now can make it seem more so.

But for anyone who’s been shown a future, then had the door slammed shut in their face, know this: this life that is happening now is not just the old one, grudgingly restarted. It is something else, newly touched by darkness, light, and love. The three of us met the man behind davebyus, a man with a calm smile and soft grey hair and open eyes, and now we walk the world with that openness. We are forever open to chance, to change, to a miracle, and this, this is our second life.

Hey James, hope you’re good.

I read this last Sunday and it really struck a chord with me. Thanks so much for sharing it. I lost my mum when I about 3 and then my dad when I was about 14. I don’t often talk about it with people and I’ve never really been able to articulate why… but this sentence absolutely nailed it for me - ‘neither Jack nor I tell it much to anyone else, perhaps because it sounds so sad that it feels like handing someone a thing they don’t know what to do with.’ It’s such a good way of putting it.

Anyway, I hope you’re doing well mate!

Theo